Can tiny microbes make birds happy?

The interconnected trio of nutrition, intestinal health and animal welfare is vital in efficient poultry production. There is a growing body of evidence that illustrates the central role played by the microbiome in maintaining the functional integrity of that system.

The interconnected trio of nutrition, intestinal health and animal welfare is vital in efficient poultry production. Commercial poultry producers are aware of this, and the vast majority have implemented standard processes and practices for crucial factors such as diet, stocking density, light regimen, air quality, water hygiene and ammonia emissions. However, stress is still a major issue in modern production systems that negatively affects the health and welfare of the birds and leads to significant economic losses. Like all animals, chickens react on multiple levels when exposed to stress. Behavioural changes such as increased pecking, fights and reduced feed intake lead to welfare issues and decreased performance.

In addition, stress also has a direct effect on the gut microbiome and on both intestinal integrity and immunity, which can lead to a variety of pathologies. However, recent advances have shown that this is a 2-way street; not only does stress affect the microbiome, but modulations of the gut microbiome can also affect the animal’s behaviour, negating adverse effects of stress.

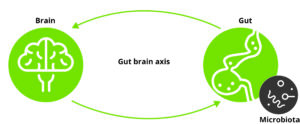

Figure 1 – Gut-Brain axis.

Gut–brain axis and the microbiome

The gut–brain axis is the bidirectional signalling between the gut and brain in animals and humans. A link between the gut and our brain seems intuitive, since we have all felt our stomachs churn and start feeling hungry. However, the existence of a gut–brain axis was first demonstrated by Ivan Pavlov in his famous dog experiments that earned him the Nobel Prize in 1904. Pavlov would ring a bell whenever serving dogs food and, after a while, the dogs would salivate whenever they heard the bell ring.

Today we know that the gut–brain axis is a complex system using many pathways to communicate. Studies have shown that chronic stress and depression affect the gut, modulating the microbiome, and are strongly associated with enteric diseases such as functional gastrointestinal disorders and inflammatory bowel disease.

However, as suggested above, we are starting to realise that not only does the brain affect the microbiome, but the microbiome also plays a crucial part in what signals are sent from the gut to the brain. An early indication of this was that gut microbiome–free mice were more affected by stress than normal mice. The effect was reversible by giving the gut microbiome–free mice probiotic bacteria. This clearly showed that their microbiome influenced the mice’s ability to cope with stress. Since these early mice studies, we have uncovered many aspects of the extraordinarily complex gut–brain axis by studying many different animals, including humans. Some aspects seem universal for all animals.

Influence of the microbiome on the gut–brain axis

The digestive tract has its own nervous system extending from the esophagus to the anus or cloaca. This system is known as the enteric nervous system (ENS) and is key to the gut–brain axis. The microbiome influences several signalling pathways involved in the gut–brain axis, including metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan metabolism, blood glucose and the vagus nerve.

SCFAs such as acetate, butyrate and propionate are the most studied gut microbiome–derived metabolites and have been shown to regulate appetite, lessen stress and even have anxiety dampening effects. Similarly, the microbial influence on the hosts’ tryptophan metabolism has been highlighted in recent papers. Tryptophan is an essential amino acid obtained from the diet and metabolised in the gut. A major metabolite of tryptophan is serotonin, which functions as both a neurotransmitter and regulatory hormone. Almost all (95%) serotonin in the body is produced by specialised cells called enterochromaffin (EC) cells, which are located throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Gut bacteria interact with EC cells, thereby modulating important host metabolic processes such as blood glucose control.

While serotonin itself is unable to cross the blood–brain barrier, recent studies suggest that the long vagus nerve, running from the brain to several organs, including the gut, plays a major signalling role in the serotonergic system. This was partly discovered by murine experiments in which specific bacteria were able to increase the level of serotonin in the brain, but most of this effect was lost when the vagus nerve had been severed.

The impact of probiotics on animal welfare and health

The high complexity of the gut–brain axis makes it complicated to study and comprehend. However, we are continuously advancing our understanding of this highly interconnected system. Importantly, we are starting to understand more about the mode of action behind the microbial effect on the gut–brain axis.

Studies have shown heat stress to have a negative effect on body weight gain and feed conversion ratio and to lead to enteric diseases such as coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis in poultry. Furthermore, stress in poultry decreases the level of neurotransmitters such as serotonin in the brain. In other animals, several studies have shown a positive effect of microbiome modulations on poultry behaviour, health and production efficiency. A study with caecal microbiome transplant (CMT) in chickens showed that CMT, including specific bacteria, significantly increased the body weight of birds and found it likely that an improved stress response played a role.

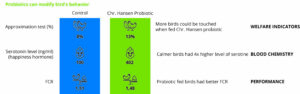

Similarly, probiotic products from Chr. Hansen have been shown to positively affect behaviour, health and production efficiency, likely via the gut–brain axis. GalliPro Fit was tested in broiler production, showing increased production performance and improved behaviour associated with significantly higher blood levels of serotonin (Figure 2). GalliPro MS has been tested in a study with layers, with similar patterns found of increased production efficiency and behavioural patterns, including less feather picking and fewer cracked eggs.

Figure 2 – Chr. Hansen probiotic impact on bird’s welfare and performance.

Click to enlarge figure

The future includes taking control of the gut–brain axis

Today, we not only realise the importance of the microbiome, but we can also change the microbiome towards a healthy state. We have already seen irrefutable evidence of the efficiency of probiotics in mitigating chronic stress, such as heat stress, but have yet to discover the full potential of probiotics on animal health, behaviour and production efficiency.

References available on request